Homes are the places we spend most of our time, especially during lockdown. Heating your home in winter can be expensive, and comes at a huge environmental cost too. Technology to make homes more self sufficient could help the UK decarbonise, while also make homes cheaper to run – something that’s crucially needed for those on lower incomes.

Housing in the UK is considered some of the poorest in Europe when it comes to energy efficiency. At the same time, homeless charity Shelter reported in 2019 that 1,157,044 British households are on the waiting list for social housing.

With this in mind, there’s a drive to improve the performance across all new homes that need to be constructed in the UK. New social housing, which is supplied to those who cannot afford to purchase or rent a home in the open housing market, can be part of the solution, by providing a safe, secure and climate resilient home for social housing tenants.

Like all other new buildings built in the UK, social housing has to comply with regulations. Currently, this includes requirements for fire safety, drainage and energy conservation. But the rules around energy conservation have not been updated since 2016, and are under review.

The new energy regulation hopes to address issues of poor insulation and reliance on heating, to ensure future homes are energy efficient with low carbon heating solutions.

Of course, homes with high levels of insulation in the walls, floors and roof will be more energy efficient. But where the energy or power comes from also matters – particularly for those on low incomes.

Homes as power stations

In 2018, 10.3% of UK households experienced fuel poverty. This means these households were in a situation where spending money on energy services would push the household income below the poverty line.

On-site renewables can be part of the solution, especially for social housing, where significant numbers of families are currently facing a choice between heat and food.

This awful situation can be avoided – or at least stemmed – by building renewable power generation and low carbon heat sources into the homes themselves, like integrated solar or thermal panels in roofs. By constructing these into the fabric of the roofs, they can be a design feature while providing a viable energy generation source for the home.

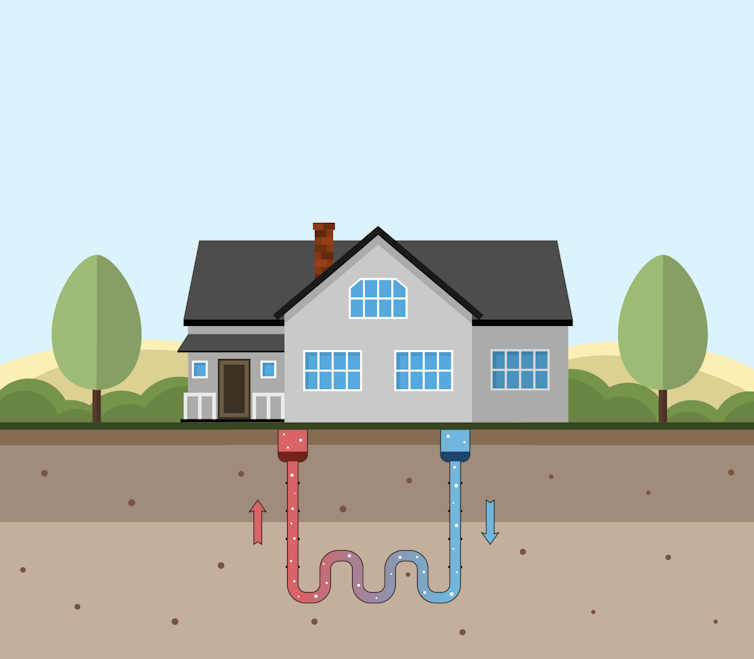

For new estates, there’s the option of wider district heating or group ground source heat pumps, which take heat directly from the ground for use in the home. Air source heat pumps can also be used in the home. This technology uses hot air from outside to heat the home as well as hot water for use – similar to how a fridge works, but in reverse.

Shutterstock/all_is_magic

A project in Swansea, Wales, is looking into using homes as mini power stations. The pilot could see more than 10,000 homes with heat pumps, solar panels and large batteries for energy storage. The results of projects like this will be vital for learning how to progress with new designs for social homes.

Wind turbines, while suitable in some rural locations, are not entirely practical for housing developments. Solar panels are much more suitable and likely to be part of the solution for decarbonising social housing – even in places which do not receive much sunlight.

Cooling

While it might be hard to imagine at the moment, in the future many people in the UK will potentially face overheating. This could cause health problems including muscle cramps, swelling and potentially heat stroke.

And so there’s also another important element to consider when making new homes in the UK climate resilient. As the climate warms, the demand for heating will go down. However, it’s predicted that the demand for cooling for homes will increase, as people and buildings overheat.

The UK climate impact projections from the Met Office report the UK will most likely see a warmer and wetter climate in the future. People in low income families are likely to be more negatively affected by this than those who are better off.

The worst case scenario for this would be the wholesale introduction of domestic air conditioning units, given their enormous demand on energy. However, there are other options to explore. Integrated design features, such as solar shading – controlling the amount of sunlight let into a building – could easily reduce the potential demand for artificial cooling.

The future of carbon reduction in the UK will need a mixture of solutions. Homes make up part of the solution to be part of a low carbon future. By building homes designed to withstand projected climate change, we can reduce the associated carbon emissions as well as preventing the potential risks of overheating as the climate warms.

By future-proofing our homes, we can address the issue of decarbonisation, fuel poverty and improved home design for now, but also for future generations, who will be the first to experience the full effects of climate change. The solutions are out there – it’s time to start implementing them.

Written by Claire Brown, PhD Candidate, Climate Change Research, University of Manchester and republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.