The chances of finding another major archaeological monument near Stonehenge today are probably very small given the generations of work that has gone into studying the site. Stumbling across such a monument that measured more than 2km across must be highly unlikely. And yet that is exactly what our team from the Anglo-Austrian “Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes” research project has done.

We discovered a circle of pits, each ten metres or more in diameter and at least five metres deep, around Stonehenge’s largest prehistoric neighbour, the so-called super henge at Durrington Walls. More amazingly, the initial evidence for this discovery was hidden away in terabytes of remote sensing data and reams of unpublished literature generated by archaeologists over the years.

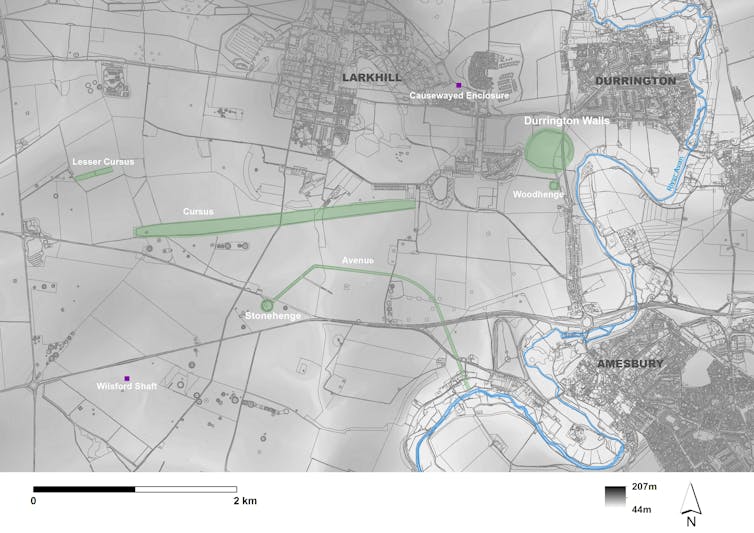

Durrington is one of Britain’s largest neolithic monuments. Comprising banks and ditches measuring 500 metres across, the henge was constructed over 4,500 years ago by early farmers, around the time that Stonehenge achieved it’s final, distinctive form. The site itself overlies what may have been one of north west Europe’s largest neolithic villages. Researchers suggest that the communities that built Stonehenge lived here.

Vincent Gaffney, Author provided

Over the last decade, there has been a quiet revolution in the landscape around Stonehenge as archaeologists have gained access to enhanced remote sensing technologies. Around 18 sq km of landscape around Stonehenge has now been surveyed through geophysics. Now archaeologists are joining the dots within these enormous data set, and making associations they might not have done otherwise.

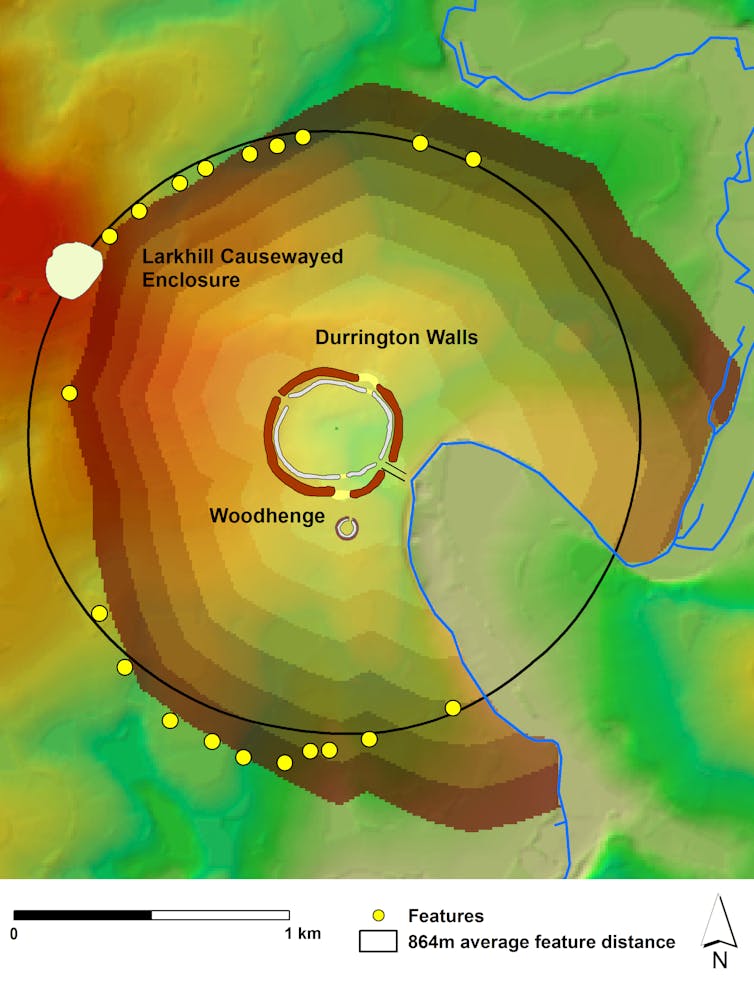

The first geophysical anomalies related to our new discovery were recorded (but not published) some years ago when a small number of peculiar circular splodges in the magnetometry data south of Durrington. These were initially interpreted as shallower features, possibly dew ponds, unlinked to the henge. But our research group realised that similar features had been recorded far to the north of the henge by archaeological contractors, interpreted as natural sink holes caused by solution of the chalk bedrock.

Our mapping work suggested all these features were actually linked and part of a single, massive circuit surrounding the henge monument at Durrington. Detailed study, including drilling for underground samples, revealed the anomalies as massive pits, with near vertical sides, containing worked flint and bone. Radiocarbon dating suggested the features were from the same time as the henge.

Shafts and pits are known in prehistoric British archaeology, but the sheer number of massive pits and the scale of the Durrington circuit is unparalleled in the UK. The internal area of the ring is likely to be at least around three sq km. This arrangement of pits certainly gives the impression they bound an important space, and here there may be a comparison to be made with Stonehenge itself.

Stonehenge actually has a territory sometimes called the “Stonehenge Envelope”. This is marked by lines of later burial mounds clustering around the monument, covering an area similar to that of Durrington Walls. The space is marked so clearly that archaeologists have suggested only a special few people may have been allowed to enter the area.

This association of Stonehenge with death and burial has also led to interpretations that it was reserved for ancestors. Durrington, in contrast, is believed to be associated with the living. But our discovery of the pits suggest that Durrington did have a similar special outer area, as large as that associated with Stonehenge.

The pit circle also provide insights into the mindset of the people who built these massive structures. The pits appear to be laid out to include a much earlier monument: the Larkhill causewayed enclosure.

Vincent Gaffney, Author provided

Built more than 1,000 years before the Durrington Walls henge, such ditched enclosures were the first large communal constructions in Britain and they were clearly important to early farming communities. The decision to appropriate this earlier monument into the circuit of the henge must have been a deliberate, symbolic statement.

In fact, the pits appear to have been laid out in a notional circle so that they were all the same walking distance from the henge as the causewayed enclosure. Given the scale involved and the shape of the landscape, which includes several valleys, this would have been difficult to achieve without the existence of a tally or counting system. This is the first evidence that such a system may have been used by neolithic people to lay out what must be considered a sacred geometry, at the scale suggested by the Durrington pits.

The unexpected discovery of a unique set of massive pits within the Stonehenge landscape may also have implications in terms of the site’s management. There are similar individual features scattered throughout the landscape that are unexplored but may be of equal significance. Yet a proposed road (the A303) development includes a road tunnel that will pass close to the iconic site of Stonehenge itself and impact a large corridor of land directly associated with the site.

The issue of value is complex when we’re discussing a period of history in which the digging of pits clearly had a multitude of social values. We would do well to consider the implication of such discoveries before a tragic loss ensues. Future generations are unlikely to forgive us if we damage this unique landscape.![]()

Written by Vince Gaffney, Anniversary Chair in Landscape Archaeology, University of Bradford and Chris Gaffney, Senior Lecturer in Archaeological Geophysics, University of Bradford and republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.